Original Article by Erica Coe, Jenny Cordina, Kana Enomoto, and Nikhil Seshan • July 23, 2021

Employees are worried about their mental health as they return to the workplace after the COVID-19 pandemic. Stigma can exacerbate their concerns, but employers can thwart its impact.

Stigma and its impact

In behavioral health, “stigma” is defined as a level of shame, prejudice, or discrimination toward people with mental-health or substance-use conditions. Because of stigma, such conditions are often viewed and treated differently from other chronic conditions, despite being largely rooted in genetics and biology. 3 Stigma affects everything from interpersonal interactions to social norms to organizational structures, including access to treatment and reimbursement for costs.

The National Academy of Medicine defines three primary forms of stigma, each of which can have far-reaching and harmful effects: 4

- Self-stigma occurs when individuals internalize and accept negative stereotypes. It turns a “whole” person into someone who feels “broken.” As one employee told us, “Depression can be a terrible illness. It makes you feel worthless and without a purpose.”

- Public stigma (which is sometimes referred to as social stigma) is the negative attitude of society toward a particular group of people. In the case of behavioral-health conditions, it creates an environment in which those with such conditions are discredited, feared, and isolated. As an employee explained, “There is such a stigma against mental-health disorders. But if you don’t talk about it, you suffer alone.”

- Structural stigma (including workplace stigma) refers to system-level discrimination—such as cultural norms, institutional practices, and healthcare policies not at parity with other health conditions—that constrains resources and opportunities and therefore impairs well-being. “The number-one challenge I face is finding [healthcare] providers,” one employee told us. “It’s a problem for me, for my wife, and for my kids.”

The impact of stigma can be profound. At a time when people are at their most vulnerable and most in need of help, stigma prevents them from reaching out. This terrible paradox can deepen an illness that is often invisible to others. Evidence-based, effective treatments that allow people with behavioral-health conditions to live productive and fulfilling lives exist. Stigma creates a cloud of shame and uncertainty that obscures what could be a clear path to recovery. 5

At a time when people are at their most vulnerable and most in need of help, stigma prevents them from reaching out. This terrible paradox can deepen an illness that is often invisible to others.

Our analysis of our two surveys substantiates that impact. For example, many employees with a behavioral-health condition indicated that they would avoid treatment because they didn’t want people finding out about their mental illness (37 percent) or substance-use disorder (52 percent). Stigma was also associated with lower workforce productivity. Close to seven in ten respondents with high self-stigma levels reported missing at least a day of work because of burnout or stress. 6

Opportunity for employers to address stigma

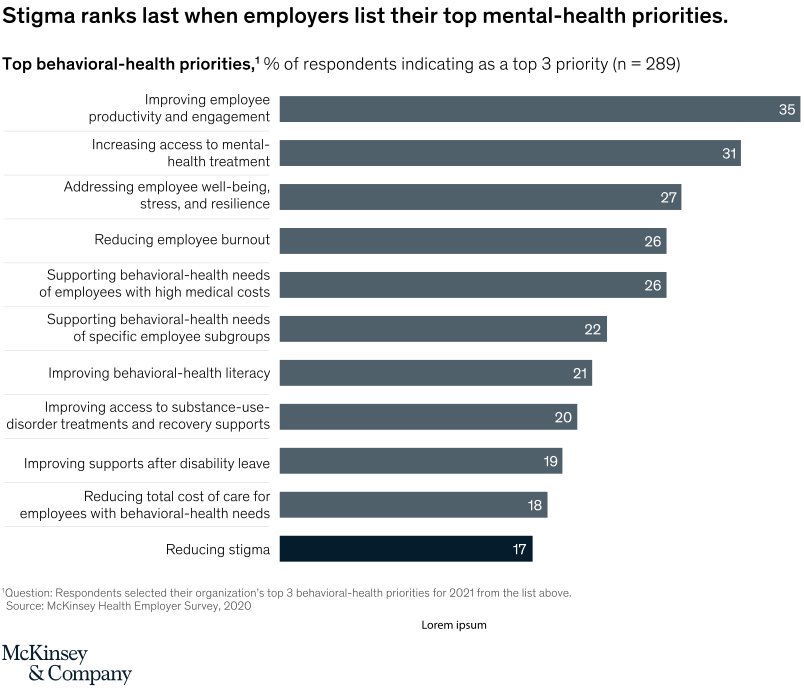

There is a pronounced disconnect between employer and employee perspectives on stigma in the workplace. While some 80 percent of the full-time-employed individuals we queried indicated that they believed that an antistigma or awareness campaign would be useful, only 23 percent of employers reported having implemented such a program. Further, when employers were asked to prioritize 11 potential behavioral-health-focused initiatives, they ranked stigma reduction last (Exhibit 1).

Yet 75 percent of the same employers acknowledged the presence of stigma in their workplaces. They know that their employees are afraid to speak up about behavioral-health needs. In fact, many leaders admit that they themselves may not be comfortable asking for help. So why aren’t they acting on what they know?

While companies may shy away from stigma because they imagine that it is too abstract to address, they are, in fact, missing an enormous opportunity. Employers can’t solve every aspect of substance-use disorders and mental illnesses in their workplaces. But stigma is something that they actually can change. Taking the right kind of actions can shift the dialogue from stigma to support.

The short window of time when organizations are evolving their operations for post-pandemic life is the perfect moment to act. Understanding, prioritizing, and planning for employees’ postpandemic mental health should be part of every company’s strategy for returning to the workplace. An inclusive culture and equitable benefits can lead to earlier, more effective intervention and support for people with behavioral-health conditions. Addressing stigma as a collective responsibility across three levels—organizational systems, leaders, and peers and teammates 7 —will make those plans far more effective and help ensure the long-term health and commitment of the workforce.

The short window of time when organizations are evolving their operations for post-pandemic life is the perfect moment to act.

Strategies for reducing stigma in the workplace

We understand that stigma can seem like a vague concept and an insurmountable challenge for employers. We also know that attitudes toward stigma can vary by demographics and other factors, making it harder to address effectively without a tailored approach. Nevertheless, those employers that have addressed stigma have modeled approaches that can work across a variety of populations. Blending their experiences and the lessons from our research, here are three overarching strategies that can help dismantle the stigma associated with behavioral-health conditions in the workplace.

Shift the perception of mental illness and addiction

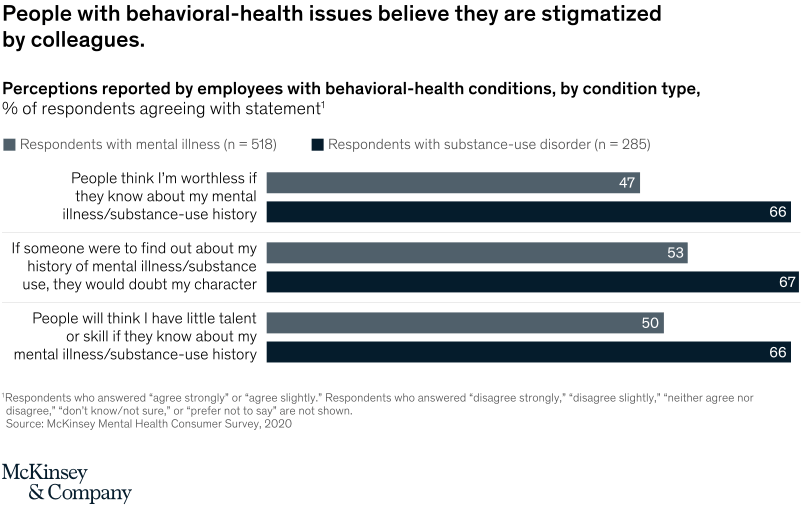

For starters, employers can change the misperception that a behavioral-health condition is a moral failing. These conditions are treatable diseases like other medical conditions. In our survey, a significant percentage of employees with behavioral-health conditions reported feeling “ashamed” or “out of place in the world” because of their conditions. Many respondents expressed worry that people would think they were worthless, or had serious character flaws, if their behavioral-health condition was known (Exhibit 2). As one employee told us, “I had a strong sense of shame, and upper management did not talk to me at all. They acted as if nothing had happened, even though the reason I had to take a leave from work was because of work-driven anxiety.” Many respondents were also concerned that colleagues who knew about their illness would doubt their talents or skills.

Companies can’t shift perceptions of mental illness by fiat. Instead, they need targeted programs that educate people and promote supportive teams. These direct actions can mitigate harmful sentiments across the company:

- Provide mental-health-literacy training to all employees. Programs such as Mental Health First Aid 8 or Just Five 9 can help people recognize and respond to behavioral-health challenges in the workplace. This kind of training spreads the message that mental and substance-use disorders are treatable conditions for which prevention, early-intervention, treatment, and recovery support can allow people to live healthy and fulfilling lives.

- Train leaders and managers to recognize signs of distress. If team leaders are educated to understand behavioral-health issues, they will be able to spot problems early and connect colleagues with available and appropriate supports. This kind of tangible support can reduce the stigma that may inhibit colleagues from asking for help.

- Use contact-based-education strategies. An evidence-based approach to education allows individuals with stigmatized conditions to humanize them by sharing their stories. Encourage leaders to share their experiences with behavioral-health challenges. This often-undertapped channel (only 24 percent of employers reported using their C-suites to communicate about mental health) can have a powerful impact across a company.

An evidence-based approach to education allows individuals with stigmatized conditions to humanize them by sharing their stories.

Eliminate discriminatory behavior

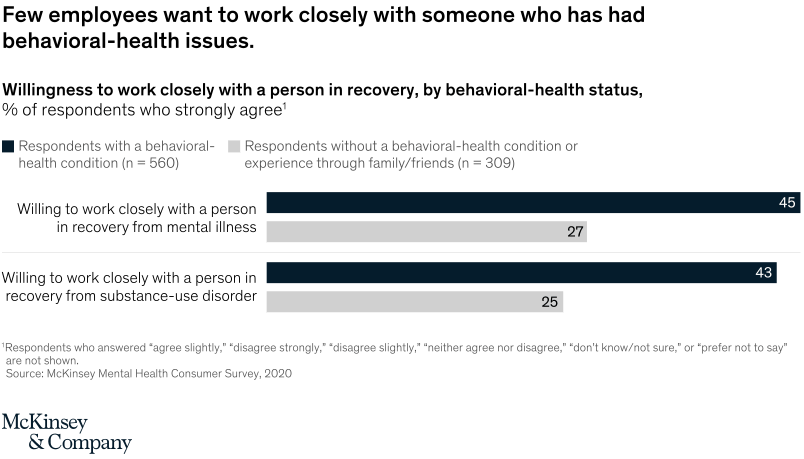

Not surprisingly, most employers agree that behavioral-health conditions should be treated with the same urgency, skill, and compassion as other medical conditions (for example, diabetes) are. Yet many employees still face prejudice in the workplace. “At my employer, there is a stigma associated with seeking out help and speaking about mental illness,” said one employee. “Maybe that’s because many workplace practices here are the reason many people feel anxious, stressed, and depressed.” Among our survey respondents, the great majority with mental illness (65 percent) or substance-use disorders (85 percent) perceive stigma in the workplace—and for good reason. Respondents who had little experience with behavioral-health conditions were far less likely to be strongly willing to work with a person in recovery compared with individuals with a mental or substance-use disorder (Exhibit 3). However, over a third of respondents who had little experience with behavioral-health conditions reported being somewhat willing, indicating a potential opportunity to reduce stigma among a substantial part of the workforce.

Policies and practices to create a culture free from discrimination are now considered “table stakes.” Employers should look closely at their workplace cultures, and many may well need to take concrete steps to ensure that their workplaces are inclusive and supportive environments as they commit to treating people with mental-health and substance-use disorders with dignity and respect. Here are some potential actions they can take to curtail discriminatory behavior:

- Commit to using nonstigmatizing language 10 across internal and external communications. For example, using person-first language that emphasizes a person’s humanity reduces stereotypes. Making the effort to call someone a “person with a substance-use disorder” instead of an “addict” replaces a negative stereotype with acceptance.

- Include neurodiversity (including behavioral-health conditions) as part of an expanded diversity, equity, and inclusion agenda. 11 Creating a supportive workplace with widely available flexibility and customization is a significant way to help people with behavioral-health conditions—disclosed or undisclosed—overcome barriers.

- Promote a psychologically safe culture. Think about rewarding an athlete mindset instead of instilling some kind of hero complex. Prioritize mental wellness as critical for peak performance instead of rewarding overwork at the expense of rest and renewal.

Strive to ensure parity among the mental- and physical-health benefits offered

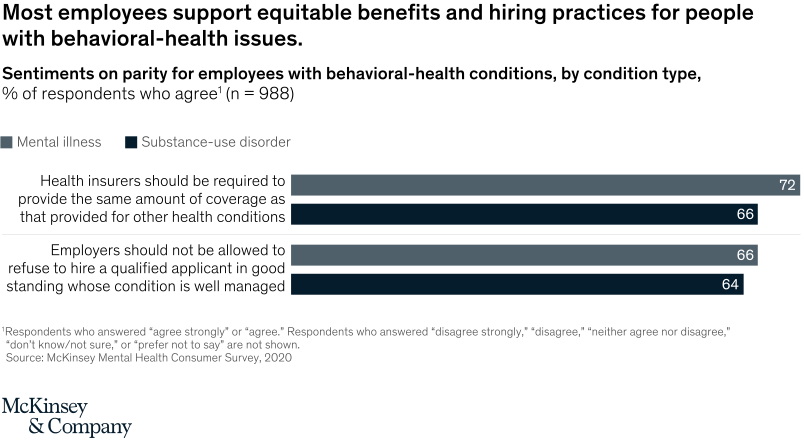

The majority of employees want their employers to ensure parity in the health plans, employee-assistance programs, and other support programs offered (Exhibit 4). Making it happen wouldn’t just be a symbolic move by employers. It would be, in fact, one of the most tangible things they could do for their workforces. As one employee reported, “Getting behavioral-health services can be incredibly challenging. It leaves me feeling very alone.”

Offering true parity in employee-support programs takes work. Companies have to check regularly to make sure that they are actually offering what they say they offer. Stigma makes the issue even more important. It takes a lot of confidence for a person to be willing to even ask for help in the first place. If they come across barriers to access, their perceptions of stigma may drive them to simply give up rather than press harder for help. One employee told us, “I got a referral for my mental illness through my employee-assistance program back in February, but the provider they referred me to was not accepting new clients. It took a lot to seek that referral, and I haven’t taken the time to request another one.”

Here are some potential actions employers can take to drive the parity of mental- and physical-health benefits they offer:

- Guarantee and widely communicate on parity. Employers can instill parity in policies (for example, return-to-work policies for individuals with behavioral-health conditions), benefits (for example, access to care and lower out-of-pocket costs), and workplace programs. They can triple-check that policies and benefits regarding behavioral-health conditions are fully aligned and then amplify and explain their availability. Parity assessments help employers benchmark the current state of their benefits and identify areas for improvement.

- Ensure equity in leadership priorities. Employers can designate and empower leaders to make mental health a priority throughout their organizations. Our survey results suggest that only 39 percent of organizations have appointed an executive-level leader who is responsible for overseeing the organization’s behavioral-health portfolio. Employers can also deepen measurement and accountability for behavioral-health outcomes, as they would for any other organizational priority. Less than half of employers reporting that they hoped to improve mental-health outcomes said they were actually measuring results.

Fewer than one in ten employees describe their workplace as free of stigma on mental or substance-use disorders. As anxious employees return to the workplace and organizations adjust to new realities after the COVID-19 pandemic, organizational systems and behaviors of leaders and employees need to change. Companies have a unique opportunity to replace negative attitudes and discriminatory policies with healthier attitudes and policies that can improve the well-being of their people.

Promoting behavioral-health literacy, creating an inclusive culture, and making mental health a clear organizational priority are no-regret moves, especially at a time when the battle for talent is getting tougher. By reducing stigma and increasing support, employers can mitigate the human, organizational, and economic costs of the pandemic-driven rise in mental illnesses and substance-use disorders.

About the author(s)

Erica Coe is a partner in McKinsey’s Atlanta office and co-leads the Center for Societal Benefit through Healthcare; Jenny Cordina is a partner in the Detroit office and leads McKinsey’s Consumer Health Insights; Kana Enomoto is senior knowledge expert in the Washington, DC, office and co-leads the Center for Societal Benefit through Healthcare; and Nikhil Seshan is a consultant in the New York office and day-to-day lead of the Center for Societal Benefit through Healthcare.

The authors wish to thank Eric Bochtler, Ellen Coombe, Drew Goldstein, Brad Herbig, Tom Latkovic, Vidya Mahadevan, Etan Raskas, Bill Schaninger, and Jeris Stueland for their contributions to this article.

This article was edited by Rick Tetzeli, an executive editor in the New York office.